Getting Wise about Water

Southern California has a bizarre relationship with water. The water that flows from your tap or garden hose in Los Angeles comes from hundreds of miles away, from the Owens River Valley, from the Colorado River, or from the State Water Project which is basically the Sacramento area. Meanwhile, all the rain that falls here locally on the city each year is treated like a waste product. It is whisked away as fast as possible, off our properties, into the storm drains, and out into the ocean (where each year its chemistry and pollutants cause great disruptions to ocean life).

Over the past few years, California has experienced droughts severe enough to merit water use regulations. Residents complained – a lot – but in our classes at the Community Garden we point out that some of the regulations are wise gardening practices anyway, and that water consciousness is the new normal.

Climate change is shifting our rainfall patterns. Rain will fall in different places – not necessarily in the locations and quantities that our massive water collection infrastructure has been built to collect. The Union of Concerned Scientists forecasts that in future decades, Californians will have only 70% of the water supply we do today, and that’s the best case scenario. If we keep emitting greenhouse gasses at business-as-usual levels, we may change the climate so much that by 2070 Southern California may have a mere 10% of the water supply we have today.

Pumping and processing water in California takes lots of energy: 18% of the state’s electricity. Thus saving water means saving energy as well. Since nearly 64% of the state’s electricity is derived from fossil sources (18.2% from filthy coal and 45.7% from not-much-better natural gas ) saving water becomes another big way to cut greenhouse gas emissions.

As we leave the era of cheap oil, how will we maintain our water infrastructure? How will we keep those vast pipelines operational? Sure, the Romans made aqueducts without the benefit of fossil fuels-driven vehicles to repair and rebuild them. How will we do it amidst an era of severe economic contraction? In James Herbert’s novel Dune, characters were forced to stretch far beyond water “conservation” – they had to develop moisture consciousness.

No matter which way we look at it, the answer remains the same: the days of opulent water consumption are now over. The ways of the future include expanding our water sources with localized rainwater harvesting, changing our water use habits to reflect appropriate use, embracing extreme conservation, and changing our attitude about “waste”water.

That said, how do we go about getting high yields in our urban agriculture despite limited water resources? Oddly enough, the answers don’t begin with drip fittings and hose-end nozzles. The answers begin on the drawing board, when you’re planning your garden. And like everything else in organic gardening, the answers begin with the soil – rich, healthy, live garden soil.

We have a misleading expression in our language in that we say “I have to go water my plants.” The more appropriate phrase would be “I have to go water my soil.” Recall the soil critters we talked about in Chapter 3. As we water our garden, our goal is to keep those soil critters happy.

Organic material within your soil acts like a sponge. It will soak up water and hold it in the root zone for soil critters and roots alike. When the sandy soils in my Westchester garden and at the Community Garden at Holy Nativity get dry, the particles within the soil merge together and make a tight surface. When you water that overdry stuff, the water beads up on the surface and runs off, leaving the soil mass as dry as ever. As clay soils dry, the soil particles clump together in heavy, thick clods. Deep cracks form between the masses. When you apply water, it runs down the cracks and fails to penetrate the clods.

Start building your soil. Add plenty of organic material – live homemade compost, or store-bought if you have to. Compost feeds your soil critters, plus serves as a “sponge” to hold moisture.

Mulch is the fluffy quilt on top of your growing beds. It helps slow evaporation, thus slows water loss from your soil. In late spring, when the weather begins to warm up and the nights are no longer as cool, it’s mulching time. Mulch everything. Put a thick blanket of material across your entire garden. Remember Emilia Hazelip: Nature abhors bare soil.

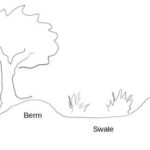

The grading of your soil – the hills and dales and earthforms — are important too. Photos of the fields of Kansas have mislead us into thinking our gardens should be flat. But we don’t have giant combines, thus we don’t necessarily need flat. As you’ll see in the rainwater harvesting section, sculpted earth forms can be an important tool.

Garden catalogs promote raised beds, but in our Southern California dry season, a raised bed is an isolated block of soil exposed on five sides to the drying influences of the air. It simply doesn’t make sense.

Here in Southern California, we should be doing the opposite. We should take a lesson from the Anasazi of the desert Southwest and use sunken beds. Sunken beds are only exposed to the drying air on one side – all the other sides are enclosed by Mother Earth. At my home garden and in the Community Garden at Holy Nativity, we have been experimenting with planting in depressions in the earth.

Return to Table of Contents