Raised beds vs. Sunken beds

With effusive and glorious terms, the garden catalogs and East Coast garden magazines try to persuade us that “to be a successful vegetable gardener you need raised beds.”

With effusive and glorious terms, the garden catalogs and East Coast garden magazines try to persuade us that “to be a successful vegetable gardener you need raised beds.”

Not in Southern California.

Consider what is behind those arguments: a drive for commercial sales, and a dramatically different growing climate.

East Coast gardeners raise their beds for two good reasons: (1) to be able to dig the soil sooner after a cold freeze, and (2) to keep the rootballs of their plants high so they won’t rot during extensive summertime rainfall. Neither of these is an issue here in Southern California. Thus their logical solution — raised beds — isn’t a good match for our Southern California growing conditions.

In our climate, for at least six months of every normal year we can expect zero rainfall. Our air is very dry, and dry air dehydrates our garden soil. We have the opposite conditions from those East Coast gardeners. Rather than risk of rot, we have perpetual drying influences. And with aridification, it’s getting even worse.

Here in Southern California, rather than raised beds, we would do better to take a lesson from the Anasazi Indians. The Anasazi grew in desert conditions, even drier than L.A. They planted their crops in diamond-shaped depressions in the earth. Each diamond was tilted to direct every bit of dew or chance precipitation toward the plant (Jane Nyhuis, Desert Harvest).

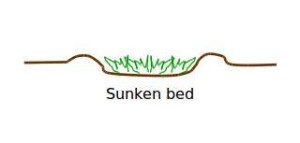

Admittedly we don’t need to go quite that far; we don’t need a diamond depression for every plant. But in my home garden and in the Community Garden at Holy Nativity, I have been experimenting with sunken beds. They are difficult to photograph (hence the little line drawing instead), but I have been building mini-berms around small sunken growing plots. This prevents irrigation water from running off into pathways, and forces the water to infiltrate.

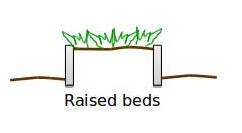

With a raised bed, your soil unit — and thus your plant’s rootball — is raised up into the drying air. It is surrounded by drying influences from five sides. It becomes very difficult to maintain healthy, moist garden soil, filled with lots of organic matter. Your soil critters experience extreme hardship.

With a sunken bed, your plant’s rootball is nestled into the protective arms of Mother Earth. That rootball is only exposed to drying influences on one plane, the top surface. And that top surface can be protected with mulch or shaded with plant canopy.

In this photo, from Native Seeds/Search, you can see clearly what sunken beds look like. For vegetable crops, you should add mulch to the surface of your soil after you form the earthen berms.

I can think of three cases when raised beds might be necessary in Southern California:

(1) If a soil test indicated excess concentration of a major toxin such as lead. (An important note: in this case, your “raised bed” needs a bottom on it, because what you really need to be doing is large-scale container gardening in order to isolate your plants from the toxins.)

(2) If your property has extreme clay or rock conditions, and you’re trying to grow food while you’re remediating. In this case, your raised beds are properly a temporary situation, because your emphasis should be on adaptation and remediation.

(3) If you, or the gardener you’re designing for, has a physical disability which prevents stooping. In this case, your “raised bed” is likely a serious structure, raised 18″ to 24″, possibly with a flat seat at the top of it.

In most instances I can think of, raised beds in our climate are a waste of money, materials, and water.

Too often people come to my garden classes to say “I’ve built my raised beds. Now, where do I get good soil to put in them?” Why create this problem?

Instead, cultivate and build your native soil and don’t raise those beds in the first place.

Find more tips on water savings in my booklet Water Wisdom for High-Yield Gardens. Or learn more about Soil Building in Southern California in my ebook The Secrets of Soil Building.