Grading

No, I’m not talking about school days. Rather, this is about grading land and using earth form to help you with water savings.

The fallacy of flat

As a kid playing in the rain, you knew precisely where to find water. There wasn’t much of it on the flat. Water gathered in puddles, and those puddles formed in depressions. A street gutter. A pothole. A footprint in the mud. Rain that fell on flat surfaces like sidewalks and driveways ran away far too quickly to be very useful for splashing games.

Photos of the fields of Kansas have mislead us into thinking our food gardens should be flat. But we don’t use giant combines in our urban gardens, thus we don’t necessarily need flat. In fact, with our Southern California water issues, not-flat might turn out to be far wiser.

Our local history with “flat” comes from what was easy and profitable for developers. Bulldozers and earth movers scalped most of our newer suburban neighborhoods into flat plains, quite different than the miniature hills and gullies created by Mother Nature.

As a kid, you knew that water runs downhill. Always. As quickly as possible. If you created channels between descending puddles, you could make a miniature river. A fast river pulls dirt particles with it. As adults, we call that erosion.

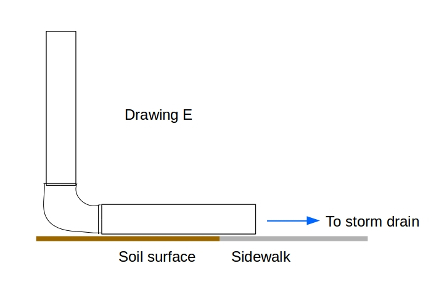

In dread fear of erosion and flooding, architects in the past decades created designs where “flat” sloped ever-so-gently toward streets, which ran to storm drains. The goal back then was to send water “away” as quickly as possible.

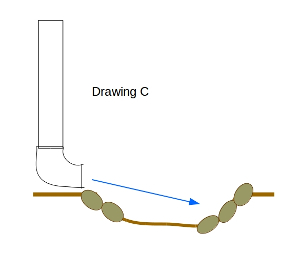

In a climate where water is precious, in an era when it is getting even moreso, it is time to cut the ties to our history with flat and embrace your childhood understanding of the realities of water. If you want to keep water on your property, you need to create physical depressions to hold it there.

Sculpted earth forms cause water to linger. We want to control runoff and erosion, and to enhance infiltration. Infiltration simply means water soaking into the soil.

Once you embrace the idea that “flat” is not necessarily the only way to garden, the world of not-flat opens to you.

I will describe several ways to create “not flat” on your property, starting with large-scale and continuing in decreasing scale.

For larger-scale earthforms, you may need a tractor, or at least a team of people, to install them. You also might need some professional expertise. You can turn to knowledgeable landscape architects or to Permaculture-trained designers for help.

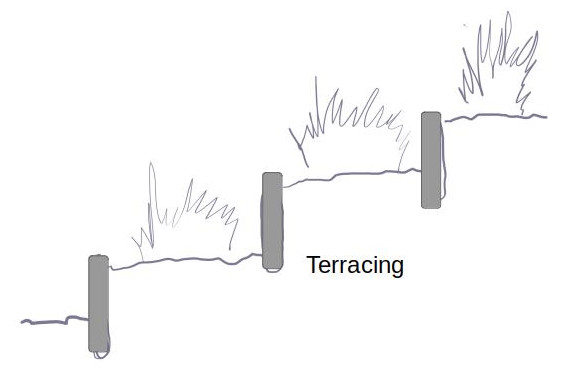

Terracing

For hillside plantings, terracing is the logical choice. Mankind has used terracing for centuries. Look up aerial photos of Huayna Picchu in Peru (you might know the famous site by the name assigned by American explorers: Macchu Picchu). In many places in Italy, the old gardens are terraced on rocky hillsides.

Terracing breaks the slope of a hill and creates cupped spots for growing. Water no longer surges downhill, bypassing plants and causing erosion. Instead, the terraces slow the water’s descent, spread it across the growing spaces, and give it a chance to infiltrate.

Swale and berm

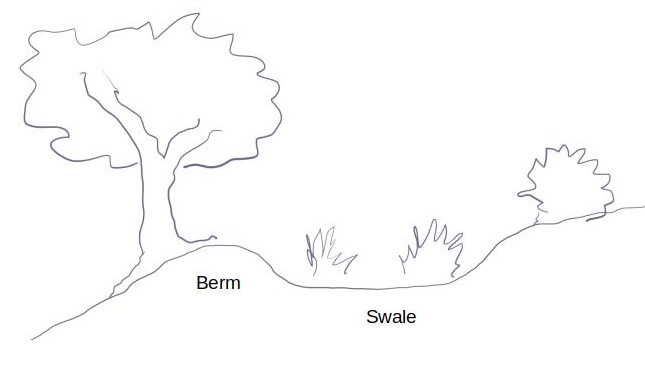

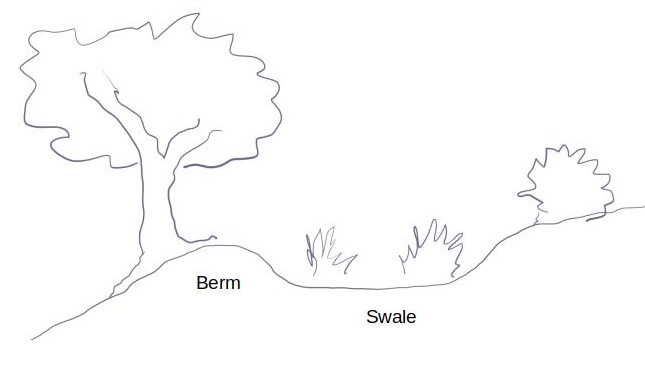

Swale-and-berm combinations are simple, low-tech ways of sculpting the earth when your slope isn’t very severe. A berm is an elongated earthen bump or mound. A swale is like a trench on the uphill side of the berm.

The swale and berm pairing is oriented to run “the long way” across your slope, follow the geographic contour lines of the land. This practice is known as keylining. Think of how the lines run on a topographical map or hiker’s map—they wrap around the hill, each line following a given elevation.

In this way, the earthen forms pause water’s downhill flow and create small depressions in which your plants can take hold. Trees or deep rooted perennial plants are often used to help preserve the form of the berm.

For most mild urban slopes, a simple earthen berm and accompanying hollow might be sufficient. I use this combination, in small scale, for new plantings of xeriscape perennials. Over time the earthen berm will erode and become a gentle slope again, but by that point your plant will be established and its root structure will begin to handle the water-catching.

Gabions

Sometimes it is necessary to reinforce an earthen berm by integrating some durable materials into the berm portion. A gabion is a roll of rocks enclosed in wire mesh.

Small-scale gabions can be used to give solid and more-lasting form to the inside of a berm. In an urban Pacific Palisades garden I designed, we created mini-gabions: We filled rolls of chicken wire with coarse gravel. We used these mini-gabions to give form to, and longer life to, a series of tree basins down a gentle slope.

Just like with swales and berms, your gabions need to be oriented “the long way” across the slope.

Piggyback the construction

Installing a larger earthforms like terraces, swales and berms can be a significant project. You might not jump to tackle that right away. But say your plumber tells you you’ve got to replace the sewer line from your house to the street. There’s going to be digging, and your yard will be torn up.

Instead of putting back the same-old, that’s a great time to solve some structural issues in your garden. After the plumbers are done, as you reassemble your garden, why not put it together differently—with a thought toward a water-lean future.

Small-scale grading

“My garden is flat,” you’ll tell me. But I would bet that when you water your garden, you have areas where you notice that the water runs off, it wants to trails away to some other place in your yard. On a micro scale, you have high and low spots. You can use these to your advantage.

The following “small-scale” earthforms can be installed without a tractor. You could do-it-yourself or build them with a small team of friends. As far as expertise, there are plenty of learn-and-do-it-yourself resources available.

Tree basins

Tree basins—earthen rings created around newly planted trees or shrubs—are a way to hold water near the new rootball. These are particularly useful in the first years when a tree has not yet become established. We used lots of basins as we established the mini-orchard in the Emerson Avenue Community Garden.

Over time basins wear away with watering, thus very few months they need to be re-formed. The basin should be formed with soil, not with loose mulch materials. Mulch can be sprinkled in a final quilt over top of the basin area.

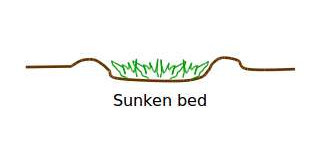

Sunken beds

See my prior post about why raised beds are not appropriate for Los Angeles climate, why we need to be taking examples from similar climates and using sunken beds instead.

- more posts about Water wisdom