Root knot nematodes

Yesterday in the Community Garden, we discovered that we are experiencing an attack of Root Knot Nematodes. The beets we pulled up had failure to thrive, failed to form a beet root, and had tons of tumor-like growths on the hair roots. Yuck.

The excess of one organism — to the point that we call them a “pest” — is a system imbalance. It’s probably due to something lacking in the overall micro-ecosystem.

I’m sure our beets this year were weakened from lack of proper rain, and from excess high temperatures this season, so they were particularly succeptible. My guess is that we probably have had low levels of root knot nematode everywhere for years, but thus far the soil ecosystem had kept them from flourishing and becoming an out-of-balance pest.

We grow organically, so that streamlines our treatment choices. The goal is to regain the soil-ecosystem balance.

About Root Knot Nematode

First, I set out to learn more about our unwelcome critters.

Here’s what we’re up against (article). These nasties “live and feed within plant roots most of their lives … They are difficult to control, and they can spread easily from garden to garden in soil on tools and boots or on infested plants.” (UC IPM)

Here’s a video from a chatty guy who goes on and on about his garden’s case of nematodes. His growing situation is quite different from ours, but we did learn a few things.

My sister dealt with root knot nematode in her vegetable garden a few years back. She too, had a growing situation which is a lot different from ours. At that time, for organic matter, she wasn’t using much homemade compost, so was using a lot of (probably chemical-laden) crop debris from nearby farms. Her growing environment is also consideraby hotter and drier than ours. The internet solutions didn’t work for her, so she ended up solarizing her soil, wiping out all her soil biota, and starting over. At the Community Garden, we hope to avoid doing that.

The general drift I got from reading multiple sources is the root knot nematode problem appears to flare up when a garden has dry conditions, hot conditions, and low-organic-matter conditions. You don’t ever get rid of root knot nematodes, so it appears that the only choice is to bring them into balance with other elements of the ecosystem.

Right now our out-of-control conditions seem to be limited to a few beds (D1, D2, A4) . Beets in nearby beds (C1) were healthy and formed normally.

A Multi-pronged Solution

For solutions to most pests (snails, aphids, cabbage white butterflies), I tend to look to the health of the ecosystem — what can I to to stimulate the ecosystem so that Mother Nature takes care of the problem, and keeps things in balance? I’m not looking to annihiliate the pest, but rather to beef up the predators, increase the strength of the plants to resist it, etc.

There are many organic recommendations on various websites. We will be trying a multi-pronged approach to the problem:

- Marigolds as green manure. Tagetes patula, Tagetes minuta, and Tagetes erecta are supposed to be the best. UC IPM says “The effect of marigolds is greatest when you grow them as a solid planting for an entire season.” The chatty video guy says to grow them a foot or so high, and then till the marigold plant material into your soil. (Note: apparently ‘Lemon Gem’ doesn’t work, and marigolds aren’t effective against the nematodes that gardeners in cold winter climates have, but that’s not us). Scholarly resources say you have to match the marigold species & variety with the kind of soil pest, and that marigolds are more effective while growing than once they are tilled in. We will try growing an intensive crop of several types of marigolds across the 3 problem beds, to till in later in summer 2015.

- Marigolds as a compost crop. We will also fold marigolds into the combo of plants we habitually use as borders/beneficial insect plants throughout the entire garden. I hope this will serve dual purpose: possibly giving some (limited?) protection to the other beds in our garden this season, and working much more marigold material into our garden’s overall compost system.

- Sanitation. Starting immediately, we’ll put any plants from the affected beds into the black trash to get them off the site and entirely out of the compost loop. We will clean any garden tools after they are used in these beds, to prevent any further spreading of the bad-nematode imbalance to other beds, and to other gardens we work in.

- Nema-resistant crops. This summer we will plant some legume plants in with the intensive marigolds, so that we continue to nourish our soil even as we are treating it. We’ll start with blackeyed peas and Hopi lima beans.

- Crop rotation. I was getting a bit casual about our crop rotation system, but this is a potent reminder to reminder serious about it. Our crop rotation handout in English and in Spanish; our vegetable crop rotation wheel on Etsy.

- Boosting beneficial soil life #1. We will do an application of beneficial nematodes in the beds which currently aren’t showing infestation. Stationary “Sf” type from GardensAlive; Mobile “Hb” type from Arbico Organics; or “Sf + Hb” combo from Arbico Organics.

- Boosting beneficial soil life #2. We will also do an application of fungal innoculant: Root Zone Beneficial Microbes from Bountiful Gardens.

- Organic matter. We typically till fresh homemade compost into our beds with every seasonal change of crops. But all the University Extension websites I read say organic matter is key. Thus we’ll make sure to “feed our beds” as we plant the marigold + legume crop.

The backup plan

Here are some other remedies we may try in the future, if the current approach does not do the job:

-

- “Digging fresh chicken manure into a hot, dry soil, something normally to be avoided, has been shown to reduce nematode numbers.” (source)

- “Drenching with water and molasses or sugar can also kill nematodes, but will have a negative impact on soil life.” (one source; mentioned by multiple sources)

- grow Nema-resistant crop varieties. Universities have developed several vegetable varieties which are supposedly resistant to root-knot. It is remarkable that all of these vegetable varieties are controlled by the major seed suppliers — the ones we tend to avoid because they haven’t signed the Safe Seed Pledge.

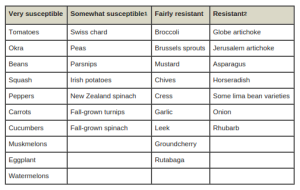

- grow nema-resistant plants. We may simply shift our focus in affected beds to plants which in general tend to have nematode resistance. (For better resolution, click on chart for hyperlink to source site)

- focus on Cool Season harvests, because nematodes are less active then, thus tend to do less damage to cool season plants.

- try other bio-fumigant green manure. Other plants that “contain high levels of bio-fumigant compounds include: rapeseed (canola) Brassica napus, BQ Mulch, and Indian mustard.” (source)

- Organic matter + green manure. “Organic matter can also be introduced into the soil through planting a green manure crop such as the legumes clover or vetch, or nonlegumes, such as rye.” (Univ of Missouri Extension)

Scholarly resources that were helpful:

- National Sustainable Agriculture Information Service

- Univ of Hawai’i Extension

- Journal of Nematology

- how do parasitic nematodes work? (More than you ever wanted to know)